Jacqueline David, daughter of Maxime David and Jeanne Malvoisin, was born in Chartres, Eure-et-Loir on 26 March 1913. His father was an École Normale alumnus, a teacher of philosophy and a translator of German and English thinkers. Her parents met at the Sorbonne during classes given by Henri Bergson, philosopher and future winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. Jacqueline was their only child. Jeanne Malvoisin married Maxime David in 1909, although not without some difficulties on the part of their parents, as Maxime David’s family was Jewish. What’s more, her future husband only received a modest salary as a teacher, but the young couple were determined and settled in Avignon and Chartres. The family’s happiness proved to be short-lived when war was declared in 1914. Maxime David was mobilised, sending a last telegram that Jacqueline would find fifty years later in her mother’s handbag: ‘I’m leavinga very happy man, don’t worry.’But he died for France on 2 October 1914 in the final hours of the Battle of the Marne. He was not the only one: two of his brothers and Jeanne’s brother would also be killed. The latter swore that his daughter’s childhood would not be affected by her father’s death.

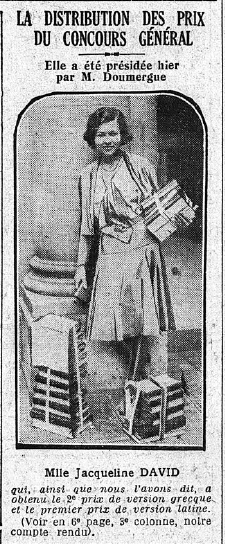

First prizewinner of the concours général competitive examinations

Here we have Jeanne David, widowed and destitute. Jacqueline was not recognised as a ward of the state until 13 March 1921. In the meantime, her mother, who had always had a taste for writing and had published short stories to help supplement the household income, picked up her pen again and published novels, while also taking on another job to support them. They moved to Paris, where her mother frequented literary and artistic circles. She had a decisive influence on the young Jacqueline, who, like her mother before her, studied at the Lycée Molière. She became the first female winner of the concours général competitive examinations, securing a first prize in Latin and a second prize in Greek. It was the first time that girls had been allowed to sit the exam This success brought with it some concern in the press about the future of a (too) brilliant young girl[1]!

Many years later, Jacqueline de Romilly would recall that time and securing that first place with humility:

‘[...] There was no Greek, so we don’t realise that these things that seem obvious to us are recent. I’ve already said this about my own life, because it’s so clear. I did Greek the first year there was Greek for girls. I took part in the concours générale the first year girls were allowed to enter the concours générale, and I was the first woman to do this or that, not because I was better than the others but because it was the first year we could[2].’

Her passion for Thucydides’ work

After completing her khâgne preparatory programme at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, she commenced her studies at the École Normale Supérieure at the age of twenty, following in her father’s footsteps. Perhaps it was on this occasion that her mother gave her an early edition of theHistory of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, marking a turning point in the young girl’s life.

In 1936, she obtained her agrégation in Greek. It was then that she began her thesis on Thucydides and Athenian imperialism. In 1939, she was appointed to Bordeaux and discovered teaching. The following year, after receiving a Catholic baptism, she married Michel de Romilly, editor of Belles Lettres. This gesture set in motion a profound process of reflection that culminated in her conversion to Catholicism in 2008. Her husband was drafted into the armed forces. With the news of the armistice, she considered moving to England, but decided not to in order to wait for her demobilised husband. The family settled in Toulouse, where living conditions were difficult, before moving to Aix-en-Provence. Soon, from one day to the next, her right to teach was taken away. The racial laws of 1941 made a crime of her paternal Jewish origins, as well as those of her husband. Jacqueline de Romilly would refer to it much later as ‘an accident of history, a temporary shame for others[3]’, but by no means a humiliation. However, she understood that she could no longer return to Paris, that neither she nor her husband could work, and that she was no longer safe. Her mother never left her side during this period, and it was under her name that the couple spent these fearful years. They hid first at her husband’s house in Aix-en-Provence, then in Aix-les-Bains and Clermont-Ferrand (where they narrowly escaped a round-up at their hotel) and finally a village in Savoie. They often had to change hiding places. To endure this period, Jacqueline found a means of escape in Thucydides and continued working on her thesis.

Following the liberation, Jacqueline de Romilly returned to teaching, starting with the Khâgne preparatory class at the Lycée de Jeunes Filles de Versailles from 1945 to 1949. For her, it was a relief to be able to take up teaching once again. At the same time, she became an ‘assistante’ (junior member of the faculty’s teaching staff) at the Sorbonne, finally publishing her thesis ‘Thucydides and Athenian Imperialism: the Historian’s Thoughts and the Genesis of the Work’ in 1947.

Professor at the University of Lille

In 1949, the Lille Faculty of Arts offered her a position as ‘senior lecturer’ and then ‘professor of classical Greek language and literature’. She held this position until 1957, while completing her teaching at the Ecole normale supérieure de jeunes filles in Sèvres. She particularly liked her job, as it enabled her to get involved in research and continue to work with the texts. Living in Paris, Jacqueline de Romilly took the train to Lille to give her classes, as did most of her colleagues at the time:

‘I’ve always lived in Paris. In fact, all the teachers in Lille made the trip and it was a very friendly atmosphere. We spent a good bit of our lives on the train. In fact, when I was awarded the palmes académiques, the dean presented me with my award in the train corridor![4]’

In 1953, she began editing and translating the eight books of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, a project that took her twenty years to complete. At the same time, she devoted several books and lectures to Thucydides. More occasionally, Jacqueline de Romilly also published fiction, first under the pseudonym Jacqueline Rancey, then under her real name.

First woman at the Collège de France

She joined the Sorbonne in 1957, where she became director of the Greek Institute in 1968. Although she didn’t have to endure any occupancy of the premises during this turbulent period, she would later admit that she had underestimated the magnitude of the changes that lay ahead:

‘Discussions with students revealed a real problem. A problem that turned out to be more serious than I thought at the time. [...] I thought there would be an explosion and then it would go back to the way it was, but it never did[5].’

In 1973, she became the first woman to hold the Chair of Ancient Greece at the Collège de France.

‘Professors at the Collège de France undoubtedly voted for me because I was a woman, much more than because of my Greek, which they couldn’t care less about. So I took advantage of it, but I was sure there was this desire to make it clear that the Collège could welcome a woman. So it was glorious and intimidating. So Isaid to myself that I had to be worthy of it and do some thorough scientific work...[6]’

From one académie to another..

Her reputation led her to teach at Oxford and Cambridge as well as in the United States. Several universities awarded her the title of ‘Doctor Honoris Causa’, including Oxford, Athens, Dublin, Heidelberg, Montreal and Yale. She also lectured extensively in Greece. In 1975, she was the first woman elected to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, an institution she presided over in 1987. In 1984, at the age of 70, she retired and became an ‘honorary professor’ at the Collège de France. But she didn’t stop her activities and campaigned for the teaching of Greek and Latin in secondary schools. She promoted the study of the humanities through a number of associations.

In 1988, she became the second woman to be elected to the Académie française. She gave several speeches there, including ‘Teaching and Education’ in 2008, which addressed on the crisis in education in France. In 1991, she was admitted to the Académie nationale des sciences, belles-lettres et arts de Bordeaux. Her commitment to Hellenism earned her Greek nationality in 1995. The ceremony took place on the Pnyx, and in 2000 she was appointed by Greece as an ambassador for Hellenism.

From 1997 onwards, she gradually lost her sight, but continued to publish regularly and was involved in a number of associations, including the Sauvegarde des enseignements littéraires (SEL) association, of which she was president from 2003 to 2010, and the Guillaume Budé association from 1981 to 1983.

In 2006, she was awarded the ‘grand-croix’ of the Légion d’Honneur. Other awards included the ‘grand-croix’ of the Ordre National du Mérite, the ‘Commandeur’ of the Palmes Académiques and the ‘Commandeur des Arts et Lettres’, as well as the Greek distinctions of the Order of the Phoenix and the Order of Honour.

Jacqueline de Romilly was the first woman to win the concours général competitive examinations, the first female professor at the Collège de France and the first woman elected to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Yet she remained humble, and while she acknowledged that she had often been ‘the first to’ she noted that this was partly due to favourable circumstances[7]. Awareness of how exceptional her own career had been came only gradually towards the end of her career. She readily expressed her surprise at this in the many interviews she gave. Jacqueline de Romilly, a woman who had enjoyed a remarkable career, died on 18 December 2010 at the Ambroise Paré hospital in Boulogne-Billancourt.

Notes written by Marjorie Desbordes and Sarah Lagache.

Notes

[1] In response to questions from the Paris-Soir journalist, her mother is said to have replied that if the young girl passed the first part of her baccalauréat, she would ‘do her philosophy’ but that she would prefer for her to find ‘a good husband who’s not too much trouble!’ Paris-Soir, 6 July 1930 (online at Gallica.fr).

[2] Excerpt from Jacqueline de Romilly (DVD) by Ramdane Issaad, ‘La mémoire du Collège de France’ Collection, Montparnasse Editions, 2010.

[3] Jacqueline de Romilly (DVD) by Ramdane Issaad, ‘La mémoire du Collège de France’ Collection, Montparnasse Editions, 2010.

[4] Idem

[5] Jacqueline de Romilly (DVD) by Ramdane Issaad, ‘La mémoire du Collège de France’ Collection, Montparnasse Editions, 2010.

[6] Idem

[7] ‘My fate has been to be the first woman on many occasions before. It’s interesting from a historical perspective in general: I took Greek at secondary school the first year that women were allowed to take Greek, I won prizes in the concours général the first year that women were allowed to compete in the concours général, I attended the École normale de garçons d’Ulm [...] When all is said and done, I was in the right place at the right time. I didn’t do anything to make it happen. I took advantage of the fact that doors were opening for women at that time.’Online extract from Canal Académie ‘Rencontre avec Jacqueline Worms de Romilly, une grande dame du quai Conti’ 2006.

Sources

Birth certificate of Jacqueline David, 3 E 085/366, ’Eure-et-Loir Department Archives

Jacqueline de Romilly, Jeanne, éditions de Fallois, 2011.

Jacqueline de Romilly (DVD) by Ramdane Issaad, ‘La mémoire du Collège de France’ Collection, Montparnasse Editions, 2010.

<link http: www.academie-francaise.fr reponse-au-discours-de-reception-de-jacqueline-de-romilly>BNF Press website: Retronews.fr

<link http: www.academie-francaise.fr reponse-au-discours-de-reception-de-jacqueline-de-romilly>www.academie-francaise.fr