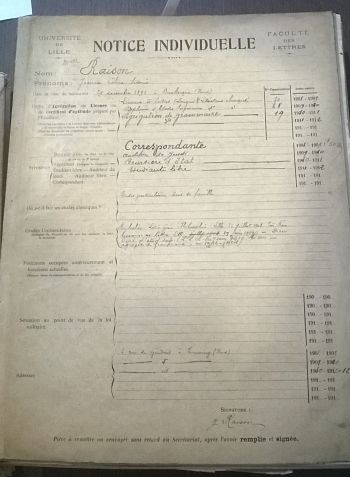

Jeanne Raison was born in Dunkirk on 29 December 1891, where her father Louis Charles Hippolyte Léon Raison was a teacher at the local college. Her mother, Eugénie Justine Leroy, was born in Lille, but they met and married in Douai. Louis’ father, already deceased, was an office manager at Douai town hall; Eugénie’s father, also deceased, was a maitre d’hôtel. They were married on 28 April 1889. Jeanne was one of the couple’s four children. The family did not stay long in Dunkirk, moving the following year to Laon, where Louis was a teacher at the secondary school. On 18 March 1895, Louis Raison was appointed grammar teacher at the secondary school in Tourcoing. It was here that young Jeanne spent most of her childhood, growing up under the attentive care of her parents, especially her father. It’s likely that Jeanne Raison showed an excellent aptitude for learning from an early age, so much so that her father encouraged her to take up classical studies (Latin and Greek), which at that time were taught only to boys. It was undoubtedly through him that she discovered her desire to teach.

University career

Since the Camille Sée law (1880), the state had sought to provide an education for women that could rival the teaching provided by the church and thus diminish the latter’s influence on minds. The development of women’s education created a great need for female teachers, and it was to solve this problem that the École normale supérieure de Sèvres was created. It was designed to prepare future teachers for the agrégation competitive exam that would allow them to provide a secondary education to girls. There was nothing to stop women from sitting the same agrégations as men, but they lacked have the necessary level of Latin and classical studies. Fortunately, Jeanne Raison could count on her father’s teaching, which provided her with the level of knowledge she required to enrol at the Lille Faculty of Arts in 1908. Pursuing a university education was not the norm. A 1908 rector’s survey counted 82 female students in the Faculty of Arts, i.e. 28% of the total. Respected courses such as the licence, DES or agrégation remained virtually closed to them. According to Jean-François Condette, female students were considered second-class citizens. Her father’s influence was evident in her choice of studies. Jeanne Raison obtained a Bachelor of Arts in 1909 and a postgraduate degree (diplôme d’études supérieures; DES) the following year. It’s worth noting that year she was awarded the 75 F prize by the Nord General Council. Despite her atypical background, Jeanne Raison was much appreciated by teachers, such as M. Potez, professor of French literature, who praised her ‘excellent, very strong spirit’ and said she ‘deserved success’. George Lefèvre lavished praise on her in an assessment from 1911: ‘With a singularly keen and clear intelligence, a literary personality more assertive than is typically seen at her age, and a wide-ranging and profound understanding of science which has not neglected more elementary and more modest knowledge and pushed it back into the shadows as it has embraced new and [illegible word] higher knowledge. Melle Raison possesses all the qualities, the faculty of elocution, clarity of exposition, great intellectual probity, natural patience and benevolence, which will make her, in a future that we can only hope and believe to be near, a teacher who honours the community of agrégés de grammaire to which she belongs.’

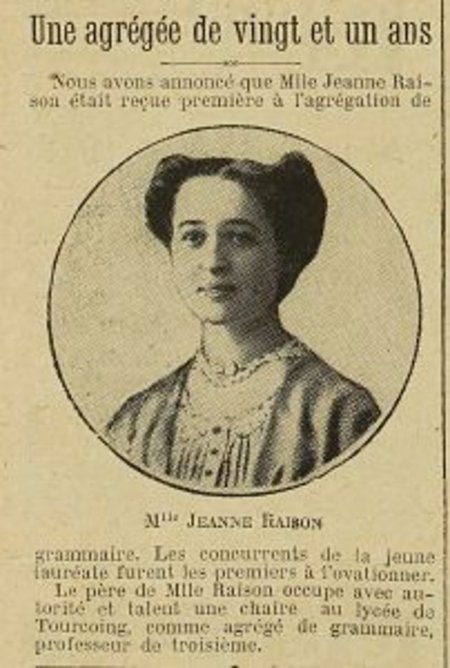

First women to pass the agrégation competitive exam for teaching grammar in boys’ schools

Jeanne Raison then decided to do something that had never been done before: sit the agrégation competitive exam for teaching grammar in boys’ schools This qualification would allow her to teach pupils in the first three years at boys’ secondary schools. She spent two years preparing for it, and came in first place in 1912. Dean Georges Lefèvre, a fervent supporter of women’s education, proudly announced in the faculty’s annual report that year that it was the first time the agrégation in grammar had been won by a woman, who had come in first place no less! ‘I am also very pleased to note that, on the list of successful candidates for the agrégation in grammar, first place is occupied by a young girl, Melle Raison, who belongs to us on two counts. Firstly, because all her preparations took place close to us, and secondly, because her father, who was also her teacher, himself did honour to the Faculty’s teaching by succeeding in the same agrégation during the 1892 competition at a young age.’

However, far from the triumph of this result, Jeanne Raison posed a serious problem for the administration. The national press widely publicised her success and questioned its consequences. Was she going to be appointed to an all-boys secondary school? Generally speaking, men didn’t want women in their institutions. The women themselves were suspicious of a competitor with such a prestigious degree. Her case embarrassed the Ministry of Public Education, which was questioned by the press about the possibility of the young agrégée teaching in a boys’ secondary school. Legally, there was nothing to prevent Jeanne Raison from requesting such an appointment, but according to the Ministry, this was not desirable. Finally, the young woman asked to be appointed to a girls’ secondary school. Initially, Jeanne was appointed to Tournon (1912-1913) before moving to the Lycée de Lille (1913 - 1917). Female teachers were victims of a discriminatory regime:

‘They had to work longer hours than men, and received a lower salary; if they had passed the agrégation teaching exam, they were not entitled to the annual agrégation allowance of 500 francs that was paid to men(3); while sick leave was counted as service time for retirement purposes up to a maximum of five years for male professors, for women, all sick leave, even when having children, was deducted(4); the women’s agrégation did not entitle its holders to work towards a doctorate(5); women did not have the right to vote in elections for the Conseil supérieur de l’Instruction publique (High Council of Public Education)(6).’

First female professor at the Lille Faculty of Arts

Like all French people, Jeanne Raison’s life was turned upside down when war was declared in 1914. The Faculty of Arts saw the departure of not only its students, but also its teaching staff who were old enough to be mobilised. Lille was soon occupied by the Germans, and the continuation of intellectual life became a way of resisting the enemy, a moral duty. The Faculty had to continue to provide courses for men who had not been mobilised, as well as for its female students (barely twenty or so). The remaining teachers were in short supply, and the dean had to recruit volunteers from secondary schools to fill in for the absentees. The need for teachers was so great that the Faculty did not hesitate to recruit female teachers, includingJeanneRaison[1]. From 1915 onwards she taught French literature. As for his father, he taught Greek instead of Latin.

Jeanne Raison quickly became a great success with her students, as George Lyon, the rector, testified in her professional file: ‘Melle Raison has definitely gained a foothold in our Faculty of Arts. Her unstinting teaching took on even greater scopeand met with ever-increasing success. Her lectures, rich in knowledge and ingeniously original, were eagerly followed by students, even those from the Faculty of Law. [...] I wish she would prepare a doctoral thesis, she’s thinking about it. And I’d be delighted to see something new: a chair of the arts in higher education held by a young woman’.

The Faculty was not spared by the war, as the buildings were repeatedly damaged by bombs. At the beginning of 1917, with fuel in short supply, the cold was such that the rector suspended the Faculty’s courses before making his private apartments available to allow them to resume. In October 1917, the occupying forces suspended traffic between Lille and Roubaix/Tourcoing, preventing some students and teachers from coming to work. Jeanne Raison and her father were in this situation, and decided to give their classes at home for students who, like them, were cut off from the university. Lille was liberated on 17 October 1918. The end of the war marked the end of Jeanne Raison’s time at the Faculty of Arts, as mobilised professors returned to their posts. Priority was given to soldiers returning to civilian life after victory. Jeanne Raison, like the other volunteer teachers, had to leave the Faculty. However, in his annual report, Dean Georges Lefèvre acknowledges the help provided by all the volunteers during this difficult period: ‘In us, however, lives on, and will live on, a deep and abiding sense of gratitude for the dedication with which they devoted rare qualities to the tasks they took on’.

It seems that this was a particularly difficult period for the young woman, as she was granted leave of absence for several months, perhaps due to the many hardships of wartime. In May 1919, she reluctantly gave up the idea of obtaining a position in higher education: ‘I realised that I was hardly likely get a job in higher education now. So I gave up the hope I had entertained at first, and applied to the Minister for an appointment in secondary education’.

An essentially Parisian career

Little is known about the rest of Jeanne Raison’s life, as there is little to be found in the archives. Louis Raison left Lille in 1922 to teach at the Lycée Buffon in Paris. Jeanne Raison followed her parents to the capital, requesting a transfer to the Lycée Fénelon in Paris. The Revue des Études Grecques lists her as a member and teacher at the Lycée Fénelon in 1933. However, Jeanne Raison maintained her links with the Lille faculty, publishing a translation of The Odyssey in collaboration with Médéric Dufour, a Lille professor, in 1935. With her parents deceased, she lived at 55 rue Vanneau in the 7th arrondissement. She in turn died on 16 June 1977 at the Laennec hospital at 42 rue de Sèvres.

Notes written by Sarah Lagache.

Sources

Nord Department Archives

- Parents’ marriage certificate - 1MiEC178R031 Douai Civil Registry

- Birth certificate - 1 Mi 404 R 006 Dunkirk Civil Registry

- Student file - 2640W634 Lille Faculty of Arts Collection

- Lille rectorate personnel file - 2T456a

Paris Archives

- Death certificate - 7D285 act 498

- IRHIS biographical data: books-openedition-org.ressources-electroniques.univ-lille.fr/irhis/117

- Annual report of the Faculty of Arts 1911-1912 and 1914 to 1919 nordnum

- Condetee (J-F), La Faculté des Lettres de Lille de 1887 à 1914 : métamorphoses d’une institution universitaire française, Villeneuve d’Ascq, Presse universitaire du Septentrion, 1999.

- Article ‘les professeurs de l'enseignement secondaire dans l’enseignement de la belle époque’ Gérard Vincent, revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine, vol. 13 no. 1 January-March 1966, pp. 49-86, available online on Persée