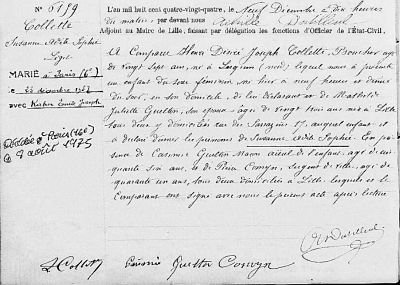

Suzanne Collette Kahn was born in Lille on 8 December 1884, the daughter of Henri Désiré Joseph Collette, a butcher, and Mathilde Juliette Guelton. Her parents lived in Lille, on rue des Sarrazins to be precise. She did her classical studies at the Collège Fénelon in Lille between 1897 and 1903, securing her brevet supérieur qualification and graduating in 1902.

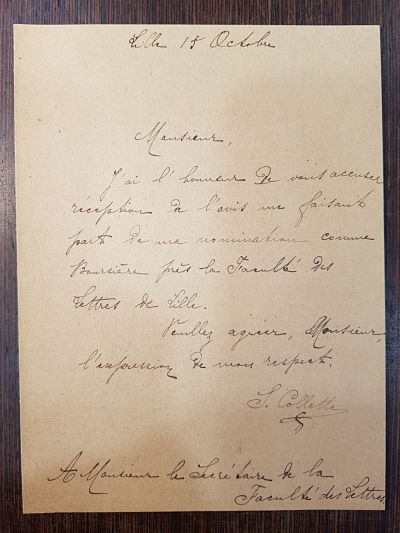

Graduate of the Lille Faculty of Arts

From 1903 to 1905, she studied for her certificate of aptitude in German at the Lille Faculty of Arts as a correspondent, then for her post-graduate degree (diplôme d’étude supérieure; DES) in German from 1905 to 1906. She was the first woman to be awarded this degree by the Faculty of Arts. From 1905 to 1907 she held a state scholarship.SuzanneCollettealso studied philosophy and became a ‘disciple’ of Victor Basch[1]. She passed her agrégation competitive teaching exam and went on to teach philosophy in the secondary schools of the provinces, before settling in Paris.

Teaching and feminism: her first commitments

Her activistactivities began in the teachers’ unions at national and international level, when she became a member of the General Federation affiliated to the General Confederation of Labour[2] and Assistant Secretary of the National Union of Secondary School Teachers and Female Secondary School Teaching Staff. She was involved in a number of initiatives and was very active in the campaign for secular education. Anactive socialist, she was administrative secretary of the SFIO’s National Committee of Socialist Women[3] in the thirties and tried to introduce special measures as part of the campaign for women’s right to work. She became vice-president of the Société des agrégées in 1936, which was founded in 1920 by Claire Suran-Mabire and whose first president was Elisabeth Butiaux. Like Suzanne Collette, she worked at the Lycée Fénelon. The struggles of this association, considered to be feminist, had for years focused on gender equality and women’s place in education. The question of preparation for the agrégation competitive examination had often been at the heart of these debates. In 1940, the Société des agrégées ceased its activities, but resumed in 1945-46 with a more masculine and uniform outlook. [4]Suzanne Collette devoted herself to defending women’s rights and suffrage, and worked on behalf of victims of injustice. She appears in several weeklies, notably Le Populaire, where she is quoted in an article about voting for the National Committee of Socialist Women.

Her career in activism with the Ligue des droits de l’Homme (Human Rights League)

Alongsideher activism on behalf of teaching, secular education and the status of women, she joined the Ligue des droits de l’Homme et du citoyen (League of Human and Citizen Rights)[5] in 1920. She contributed to the ‘Cahiers de droits de l’Homme’ (Books of Human Rights) from as early as 1923. She played an important role, becoming Deputy Secretary of the Reims section and Vice-President of the Marne federation. In 1931, she was elected to the Central Committee and became Vice-President of Section V in Paris. ForSuzanne,it was ‘one of the most enviable positions of honour and roles for a Republican woman.’[6]. From 1933 to 1939, she attended all the League’s congresses and took part in the writing and editing of several brochures. She was particularly committed to defending secular education and the civil rights of civil servants, fighting international fascism, bringing free peoples closer together and organising peace in accordance with the principles of the League of Nations. Initially a militant pacifist, she campaigned for Franco-German rapprochement, progressive disarmament and the League of Nations. Then, on the eve of the Second World War, she wrote several articles against Nazism in Cahiers des droits de l’Homme. In ‘Hitlerian Prosperity?’, an article published on 15 March 1938, she denounced Hitler’s propaganda aimed at demonstrating the superiority of the Nazi regime over democracy. In it, she analyses in detail Germany’s so-called social and economic successes, and denounces the human cost of this regime:

‘Does the individual enjoy what is ultimately as necessary to man as air and light, food and drink: freedom of movement, thought, speech and feeling? Are his rights better respected than they were five years ago? Does he find in Hitler’s Germany those guarantees of justice which constitute the very essence of civilisation? [...] It’s all very well for Hitler to pass over in silence all these questions that are being asked of him by all those who still attach some value to human dignity: there are too many glaring facts to answer them in the negative. The concentration camp regime, which has not been abolished, the police terror which is increasingly exercised over all acts of public and private life, criminal law which punishes ‘guilty intent’ with death, which makes any act contrary to ‘popular common sense’ a crime, and provides for capital punishment for eleven cases of treason, defined as ‘treason against the people’, show that in the Nazi system the individual counts for nothing.

She did it again in November 1938 in ‘Munich and Our Principles’, in which she analysed the Sudetenland crisis, the annexation of which to the Reich had been secured by Hitler. In it, she denounced the misuse of the concept of ‘peoples’ right to self-determination’, and denounced the ‘diktat’ imposed on Czechoslovakia by Germany.

‘And what are the conditions of this diktat? Under the pretext of incorporating 3 million 250,000 Germans who never belonged to Germany, the International Commission provided for in the Munich Agreement has now incorporated 850,000 Czechs, who, because they have been handed over to Hitler’s regime, have lost all their basic civil liberties, and have been deprived of the most basic human rights.

She was particularly concerned about the fate of Nazi opponents abandoned by the democracies.

‘Citizens, this is not peace; this is the infernal dance in which humanity has been struggling for millennia. These new injustices will lead to new hatreds, new revenges and new wars. This is not peace through justice and the rule of law; this is not our ideal.’

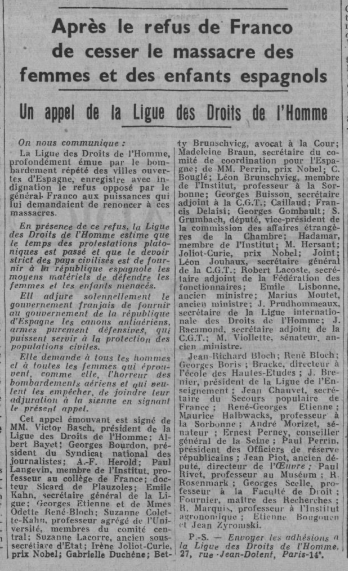

This commitment to opposing Nazism was also reflected in her support for the Spanish Republic. Along with others, she signed an appeal against the massacres of Spanish women and children, and demanded that France provide the Spanish Republic with defensive weapons to protect the population. In the weekly publication Ce soir, her name appears in an appeal by the Ligue des droits de l’homme in the article: ‘After Franco’s refusal to stop the massacre of Spanish women and children’ in 1939 (Extract from the weekly Ce soir of 18.06.1938. Source: Retronews). Shewas one of the secretaries of the Comité d’accueil aux enfants espagnols (Spanish Children’s Welcome Committee), chaired by Victor Basch and Léon Jouhaux.

In addition to being a very active figure in the League, she had been a socialist activist since the 1920s. She joined the Reims section in 1924 and the Seine federation in 1925. SuzanneCollette and Odette Bloch[7] were the only two women on the committee in 1935. They decided to write a letter asking for clarification of the League’s position on women’s suffrage. This letter was read by Émile Kahn[8] and addressed to the League President. She was also the League’s delegate to the centre féminin d’initiative pour la défense de la paix (Women’s Initiative Centre for the Defence of Peace).

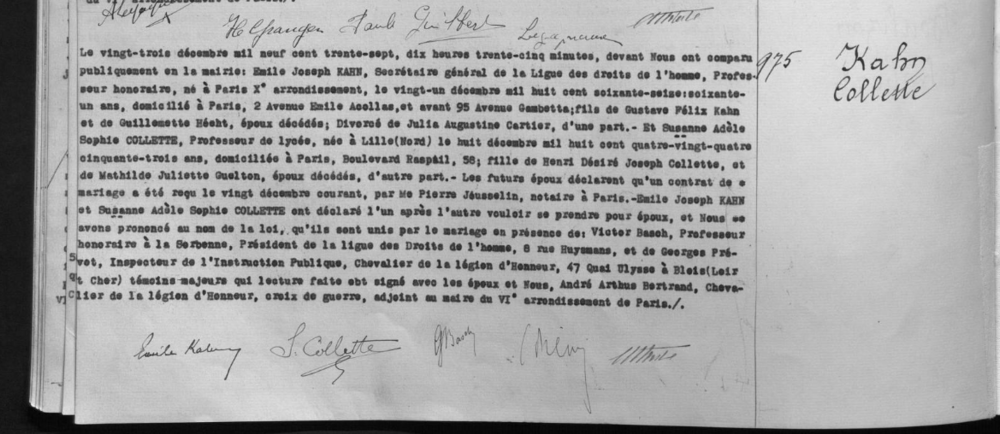

SuzanneCollette married Émile Kahn, General Secretary of the League, on 23 December 1937 in Paris[9] and offered his resignation to the Central Committee in 1938 following his marriage in order to avoid a conflict of interest within the LDH. The Central Committee unanimously convinced him to withdraw his resignation. That same year, she spoke out vehemently against the Munich Agreement of 1938. The aim of this agreement was to resolve the Sudetenland crisis and establish Czechoslovakia as an independent state. [10]

A militant pacifist, she campaigned for Franco-German rapprochement and progressive disarmament, and supported the League of Nations.

The impact of the Second World War

During the Second World War, Suzanne and her husband took refuge in the south of France, but kept in touch with their friends who were victims of repression, such as Suzanne Buisson[10] and Victor Basch. They lost much of their knowledge in the horrors of the Second World War and in the concentration and extermination camps. In addition to Suzanne Buisson and Victor Basch, Odette Bloch also died as a result of the atrocities committed at Auschwitz. Twenty years later, in 1965, Suzanne Collette Kahn wrote an article on crimes against humanity for the weekly newspaper ‘Le droit de vivre’, in which she agreed with the punishments meted out to those guilty of war atrocities.

The post-war period: the resumption of political activity

Once France was liberated, Suzanne Collette Kahn resumed her political activities and her commitment to the status of women. In fact, she was asked by the S.F.I.O. general secretariat to reassemble the national women’s commission. In 1945 she published a brochure: Woman, you are going to vote: How? She ran for the 2nd National Constituent Assembly in June 1946, but was unsuccessful. Her husband became Vice-President of the Ligue des droits de l’Homme (Human Rights League), then President after 1946.

In the 1950s-1960s, Suzanne and her husband took sides against Guy Mollet[11]andRobert Lacoste[12] concerning the policy of repression and the rejection of a ceasefire in Algeria. Suzanne returned to the League as Vice-President of Section XVI and rejoined the central committee. In 1953, she was elected Vice-President and played an active role in the International Federation for Human Rights. At the same time, she helped found the Autonomous Socialist Party (Parti socialiste autonome; P.S.A.) and later the United Socialist Party (Parti socialiste unifié; P.S.U.), as part of which she was a member of the International Problems Commission in 1960.

Suzanne Collette Kahn was an independent activist who fought throughout her life for women’s rights, pacifism and secular education. She took part in numerous debates and campaigned passionately on many subjects. This Lille-based activist can be considered a symbolic figure in the defence of women’s status in trade union and political circles. She died in Paris on 8 August 1957.

Notes written by Marjorie Desbordes and Sarah Lagache.

Notes

[1] Victor Basch (1863-1944) was a professor of philosophy and German at the Sorbonne. Along with Ludovic Trarieux and Lucien Herr, he co-founded the French League of Human and Citizen Rights. He was president of the league from 1926 to 1944. He was assassinated during the Second World War for his activism.

[2] The Confédération générale du Travail. This French employees’ union was founded in 1895.

[3] The Section Française de l’Internationale Ouvrière. This was a political party that was created in 1905 and dissolved in 1969. In 1969, the SFIO became the Parti socialiste (P.S.).

[4] See article: Yves Verneuil, ‘La Société des agrégées, entre féminisme et esprit de catégorie (1920-1948)’, Histoire de l’éducation [Online], 115-116 | 2007, published online 1 January 2012, accessed 1 October 2016. URL: http://histoire-education.revues.org/1426 ; DOI: 10.4000/histoire-education.1426

[5] The LDHC was founded in 1898 by Ludovic Trarieux. This association aimed to defend and promote human rights within the French Republic and in all possible areas.

[6] Note sent by Emmanuel Naquet and produced by Wendy Perry, an American historian whose work has not been published.

[7] Odette Bloch (1893-1943) was a lawyer and member of the LDH central committee. She died during the anti-Semitic atrocities carried out at the Auschwitz extermination camps.

[8] Émile Kahn (1876-1958) was an ‘agrégé’ in history and famous for his political career. He joined the SFIO and rose through the ranks of the LDH. He joined the central committee in 1909. He was Vice-President from 1929 to 1932, General Secretary from 1932 to 1953 and President from 1953 until his death. He died during a tour of the French provinces, following a surgical operation. Concurrently with this political career, he was editor-in-chief of Le Populaire for the SFIO, then a contributor to La Lumière for the Union de gauche. After the Second World War, he joined the editorial board of the Revue Socialiste.

[9] This was Émile Kahn’s third marriage, and the witnesses were Victor Basch (president of the LDH) and Georges Prévet, public education inspector.

[10] Suzanne Buisson (1883-1944) was a member of the SFIO from 1905 to 1920 and went on to become the long-serving national secretary of the Femmes Socialistes and editor of a women’s page in the weekly newspaper Le Populaire. She was married to Georges Buisson, assistant secretary of the C.G.T. Sadly, her acts of bravery and resistance are a credit to her. She was tortured, imprisoned in Montluc prison and eventually deported to Auschwitz, where she was murdered by the Nazis. A letter from her cellmate at Montluc prison shows the courage of this woman in the face of torture, who continued to thwart the Nazis’ activities by giving false addresses and information despite physical pressure. (Letter – Maitron)

[11] Guy Mollet (1905-1975) was Minister of State from 1946 to 1947, then Minister of State in charge of the Council of Europe from 1950 to 1951, and finally President of the Council under the Fourth Republic from 1956 to 1957. At the same time, he was General Secretary of the SFIO from 1946 to 1969. He was a key critic of its repressive policies. He appointed Robert Lacoste, Minister resident in Algeria.

[12] Robert Lacoste (1898-1989) was a French politician, trade unionist and socialist MP. He is best known for his role as Governor General and Minister of Algeria, a position he held from 1956 to 1958.

Sources

Naquet, Emmanuel. ‘La Ligue des Droits de l’Homme : une association en politique (1898-1940).’ PHD Thesis, Sciences Po - Institut d’études politiques de Paris, 2005.

Naquet, Emmanuel et al. (2014) Pour l’Humanité : la Ligue des droits de l'homme, de l'affaire Dreyfus à la défaite de 1940/Emmanuel Naquet; preface by Pierre Joxe, afterword by Serge Berstein. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes.

Yves Verneuil, ‘La Société des agrégées, entre féminisme et esprit de catégorie (1920-1948)’, Histoire de l’éducation [Online], 115-116 | 2007, published online 1 January 2012, accessed 1 October 2016. URL: histoire-education.revues.org/1426; DOI: 10.4000/histoire-education.1426

Online sources:

Morin Gilles, Maitron article on Suzanne Collette-Kahn (http://maitron-en-ligne.univ-paris1.fr/spip.php?article20363, note Collette-Kahn, Suzanne [born Collette, Suzanne, Adèle, Sophie, spouse Kahn] by Gilles Morin, version uploaded 25 October 2008, last modified 25 July 2018)

Rétronews (Les cahiers des Droits de l’Homme 1938-1940)

Archives:

Nord Department Archives – Lille Faculty of Arts Collection - 2640 W 87 (student file)

Paris Municipal Archives, marriage certificate