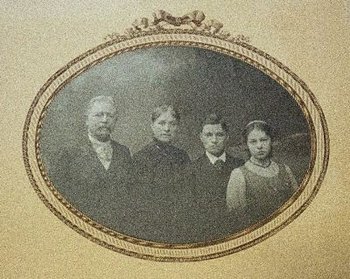

Albertine Patin was born on 7 October 1864 in Lieusaint, Seine-et-Marne. Her mother, who had come from Sarthe to find work, met Victor Patin, a shepherd from the Brie region. They married around 1844 and settled in Lieusaint(77). The couple had eight children, including Albertine, the seventh sibling.

Young Albertine was raised to be ‘upright and honest’. She lost her father in 1881 at the age of 16. As far as education was concerned, the attic of the family farmhouse, where piles of books are to be found, was a source of knowledge for her. A nun also taught her geography and all about the kings of France. Armed with this knowledge, Albertine took the entrance exam for the Melun Teacher Training College. This marked the beginning of a long period spent in such institutions, coinciding with the loss of her mother in 1885.

Head of a teacher training college aged 29

After obtaining her ‘brevet élémentaire’ qualification in 1883 and her ‘brevet supérieur’ in 1884 the following year, she became a substitute teacher in the Seine-et-Marne department(77). She then applied to the Teacher Training College in Fontenay aux Roses, Hauts de Seine(92) in 1886. Here she met her role model, Mr Felix Pécaut, founder of the Fontenay aux Roses Girls’ Teacher Training College and its first headteacher for sixteen years. In a speech she gave at the Sorbonne on 10 June 1930 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Teacher Training College in Fontenay aux Roses, she said: ‘At Fontenay, Félix Pécaut proved himself to be a great educator, and with him we experienced some of the finest and richest years of French pedagogy’.

Albertine Patin left the Teacher Training College seven years after starting there, opening up the possibility of becoming the head of a teacher training college. She asked to be posted to Oran in Algeria, where she met her future husband: Mr Eidenschenk, a school inspector from Alsace.

They married in 1894 and had two children together, Albert in 1895 and Jeanne in 1898.

After a long leave of absence to look after her children, she was appointed head of Chambéry Teacher Training College (Savoye - 73) in 1899. She then became head of the Teacher Training College in Saint Brieuc (Côtes d’Armor - 22). We don’t have much information on these periods, but she was gaining experience for her future position in Douai (59).

Douai Teacher Training College

In 1905, Albertine Eidenschenk-Patin took up her post as headteacher at the Douai Teacher Training College. This would be the longest job she would have in her career, and she would be putting all her skills to good use. His daughter, Ms Jeanne Mauchaussat-Eidenschenk, best described the atmosphere that reigned there:

‘You can’t imagine how austere that college on rue d’Esquerchin was. It was practically a convent!

It was accessed via a wide avenue, with the door to the street concealed behind solid metal panels. The intention was to isolate and cloister these young girls.

Beyond the avenue lay a second gate, very beautiful, which was never closed; but the intention was there all the same.’

Several other testimonies recount observing a strict, monastic school. Albertine Eidenschenk-Patin would implement measures to make the school less strict and more pleasant for the girls who stayed there.

Firstly, the living environment was made more conducive to study. She had the school enlarged and flowers planted in the main courtyard. It was during this period that Douai’s botanical garden became the grounds of the Teacher Training College. Madame Larrivière, a former student of the college, recounts this fabulous moment:

‘I started at the Teacher Training College in 1908. [...] An event that heralded the transformations to come occurred during my first year: the wall between our playground and the ‘tree garden’ came crashing down during a history lesson. The garden was ours! In the end, the town agreed to donate it to enlarge the school.

These changes also extended to building interiors. Albertine Eidenschenk-Patin made the school’s windows transparent, as they were previously coated with lime. This let light into the dormitories, with each student getting half a window in her room. In addition, each student was allowed to arrange her own dormitory space as she wished.

One of her most notable initiatives was to do away with the hat that formed part of the uniform. As far as the headteacher was concerned, the discretion required of normal women could not be reconciled with the wearing of this eye-catching piece of ‘headgear’.

Secondly, Albertine Eidenschenk-Patin’s teaching methods were innovative. She applied the method used by her peers at the Teacher Training College in Fontenay aux Roses. She introduced what she called ‘Morning Meetings’. These took place at the start of the day, and covered a range of subjects. Students could sing, or talk about various subjects such as literature, science or women’s emancipation. Ms Mauchaussat-Eidenschenk reports her mother’s words as follows: ‘Whatever the extent of your knowledge and teaching skills, you are not a teacher if you are not concerned with the moral education of the children entrusted to you’.

It was in this spirit of moral education that Madame Eidenschenk-Patin was elected and re-elected to the Conseil Supérieur de l’Instruction Publique (High Council for Public Education) from 1909 onwards.

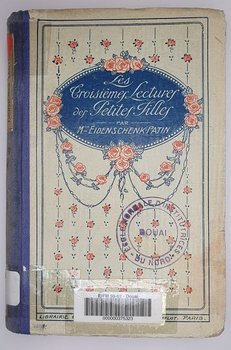

It was also during this period that she published the first volume of her ‘Young Girls’ Readings’. She published three between 1911 and 1913.

Albertine Eidenschenk-Patin gives us an idea of the value of her work on page 379 of her third book, ‘Young Girls’ Readings: Volume Three’:

‘As I close this book, young girls, for whom I have written it, I think of you and try to guess the thoughts and feelings it has aroused in you. [...] But I don’t want these emotions to be fleeting and sterile. Otherwise it would be better not to experience them at all. They must lead you to act in accordance with what you have felt. You must never let a flutter of pity die out in your heart without looking around you for an opportunity to show kindness to someone, be it man or beast. You must not let any flicker of admiration or enthusiasm die out in you without striving to reach the level of the things you admire, by showing a little heroism yourself.’

Albertine Eideschenk-Patin would have to prove her heroism in the coming Great War.

The Great War and the end of her career

In 1914, the men in the family went off to war. Mr Eidenschenk applied for reinstatement in the army as an interpreter. The son, Albert, was 19. He enlisted and left for the front in January 1915.

In the meantime, Albertine Eidenschenk-Patin took care of the girls studying at the college in Douai. The Girls’ Teacher Training College was occupied by the German army and had been used as a Bavarian field hospital since 1914. In 1916, she succeeded in getting a small group of college students to pass the ‘Brevet supérieur’ examinations. In 1917, she learned of her son’s death on the battlefield from wounds sustained on 22 June 1916. Here is an excerpt from her son’s last letter: ‘Remember that although I was a good soldier, I was a pacifist and wished that this terrible war would be the last. May all those who seek to realise this dream and rid humanity of this scourge be united in their efforts’ (‘Une femme de bien :Mme Eidenschenk - Patin’, La Française, 1938)

Tired out by the occupation and the news of her son’s death, she leaves Douai for Dax in the Landes region to work as a primary school inspector.

In October 1918, she became headteacher of the Teacher Training College in Toulouse. She remained there for a short time, returning to her post at Douai Teacher Training College for Easter 1919. That same year, Laurent, her husband, died of Spanish flu after being demobilised.

She found herself alone with her daughter in a school ruined by war, but she would put all her energy into bringing it back to life and establishing values for future groups of students.

She was involved in this reconstruction work until her retirement in 1926. After that, she would return to Aisne to rest, but she wouldn’t remain idle for long. Albertine Eidenschenk-Patin wanted to pay tribute to her son and all his comrades in arms, so in 1928 she createdThe International League of Mothers and Educators for Peace (La Ligue internationale des mères et éducatrices pour la paix; LIMEP).

She is joined by Ms L. Bouniol, Ms Marie Lucas, Ms J. Forsans and Ms M.-J. Prudhommeaux. Three of these five women lost a son in the war. Our teacher training college headmistress is its first president, and the league’s aim is clear: ‘Mothers and educators must be instructed in international problems in order to enlighten and strengthen their desire for peace and give them the opportunity to counter the objections of those who oppose reconciliation between peoples’.

In the year following its creation, a network of correspondents recruited from the teaching world was built. First published in France, the ‘Les Peuples Unis’ newsletter was soon distributed internationally in England, Belgium and Germany. In the early 1930s, the number of female members grew exponentially: 60,000 in 1932, 80,000 in 1934.

Even in the League’s articles of association, we find the ideas that led Albertine Eidenschenk-Patin to speak out in many countries: members must ‘fight against the causes of war in union with the whole League’, or ‘bring up their children or pupils in a spirit of benevolence and cordiality towards foreigners, whoever they may be, and to repress in them the instincts of violence and brutality’.

Despite all the League’s efforts to promote peace and disarmament, fate caught up with it and the Second World War broke out. Albertine Eidenschenk-Patin would then stop her activities to look after her family. She died in 1942. She was laid to rest beside her son in the Berny-Rivière cemetery in the Aisne department.

During her lifetime, Albertine Eidenschenk-Patin and her values were appreciated and honoured. After her death, this admiration continued with the creation of the Eidenschenk Foundation in 1947. The Foundation enabled college students to take part in cultural stays or summer camps. It wasn’t until 1993, shortly after the Teacher Training College was replaced by the Institut Universitaire de Formation des Maîtres (University Institute for Teacher Training), that the foundation became the Association à la Mémoire de Madame Eidenschenk et des Écoles Normales (Association in Memory of Ms Eidenschenk and the Teacher Training Colleges).

Meanwhile, on 5 December 1986, the ‘Espace Eidenschenk’ exhibition room was inaugurated at Douai Teacher Training College. Ms Brisville, then president of the Alumnae Association, began her speech with this tribute: ‘So I’m going to talk about this remarkable woman, who, thanks to her bold personality, left her mark on 21 graduating classes of Douai Teacher Training College.’

This exceptional woman has left an indelible imprint on the history of student teachers. Officer of the Legion of Honour, member of the conseil supérieur de l’Instruction civique (High Council for Civic Education), founder of the ligue internationale des mères et des éducatrices pour la paix (International League of Mothers and Educators for Peace), but beyond her distinctions and commendable role, it is the singular and innovative career of a woman of her time that we must celebrate. A woman who put women at the heart of her actions.

Notes written by Alexis Ballart

Bibliography

Albertine Eidenschenk-Patin biography resources

Doucet, Marie-Michèle, Prise de parole au féminin : la paix et les relations internationales dans les revendications du mouvement de femmes pour la paix en France (1919-1934),thesis – University of Montreal, May 2015 ">https://papyrus.bib.umontreal.ca/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1866/13597/Doucet_Marie-Mich%C3%A8le_2015_Th%C3%A8se.pdf?sequence=8&isAllowed=y>

Albertine Eidenschenk-Patin’s publications

Drevet, Camille,Sur les routes humaines, preface by Madame Eidenschenk-Patin (dated 1936), Paris, S.D

Eidenschenk-Patin, Albertine, Les troisièmes lectures des petites filles, Paris, Ch. Delagrave, 1913

Eidenschenk-Patin, Albertine, Les Deuxièmes lectures des petites filles, Paris, Ch. Delagrave, 1912

Eidenschenk-Patin, Albertine, Les premières lectures des petites filles, Paris, Ch. Delagrave, 1911

Eidenschenk-Patin, Albertine, Variétés morales et pédagogiques. Petits et grands secrets de bonheur, Paris, Ch. Delagrave, 1913

Sources

Amicale des Anciennes élèves de l’école normale d’institutrices du Nord, Madame Eidenschenk, Douai Imprimerie du CRDP, 1978

Amicale des anciennes et anciens élèves de l’école normale d’institutrices de Douai semi-annual newsletter, No. 114, January 2018

Amicale des anciennes et anciens élèves de l’école normale d’institutrices de Douai semi-annual newsletter, No. 97, March 1994

Amicale des anciennes et anciens élèves de l’école normale d’institutrices de Douai semi-annual newsletter, No. 91, March 1987

Amicale des anciennes et anciens élèves de l’école normale d’institutrices de Douai semi-annual newsletter, No. 86, March 1982

Education Authority personnel file, 2T265 Nord Department Archives

Douai postcard (give references)

Military service register, FR ANOM 2 RN 167 Archives of France