Amélie Alphant was born on in Saint-Omer on 19 March 1901 in Saint-Omer. She wasborn at the home of her maternal grandmother Amélie Lagroua (maiden name Derbesse)[1]. Her mother Blanche, 31, did not practise a profession. Her father, Auguste Alphant, aged 46, was absent. He lived in Paris’11th district. He travelled to be with his family immediately after Amélie’s birth, as he is registered at Amélie Lagroua’s home, 21 rue Louis Martel in Saint-Omer, when Amélie was 5 days old.

A native of the Vaucluse region, Auguste Alphant worked for the French postal service, moving from town to town as required by his job.After a spell as a postal clerk in Marseille, he enrolled at the city’s Faculty of Law and obtained his bachelor’s degree. A senior postal clerk in Paris at the time of his marriage in 1899, he was transferred to Hazebrouck after the birth of his daughter, before being appointed postmaster in Saint-Omer in 1905.

Amélie Alphant’s mother, Blanche, came from a notable Saint-Omer family. Her grandfather, Anschaire Derbesse, was a local councillor. Blanche Lagroua never knew her father, Guillaume Lagroua, a soldier who died a few months after her birth. She attended Mademoiselle Lartizien’s boarding school in Saint-Omer, where she passed her primary school certificate in 1883 and her elementary school certificate in 1888.

A childhood in Auvergne and Flanders disrupted by the war

Like her mother, Amélie Alphant grew up in Saint-Omer. She had fond memories of her childhood in Auvergne. She attended the local school, which she described as ‘dilapidated’. However, she really enjoyed it, making loyal friends and appreciating her teacher’s style of teaching.Amélie Alphant and her father shared a strong bond, with the latter providing constant support in everything she did. They took many walks together in the public garden, ‘one of the most beautiful in the region’.

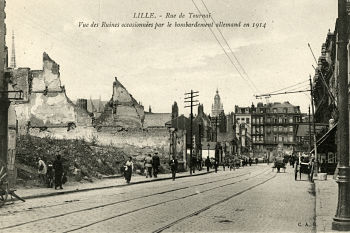

In 1911, Auguste Alphant was appointed postmaster at the Lille-Gare office on rue de Tournai. Amélie Alphant continued her studies at the Lycée Fénelon. She found it difficult to adapt to this new school, which she considered too rigid. She missed the simplicity of her fellow pupils in Saint-Omer.

During the Great War, Amélie Alphant found herself separated from her father. She and her mother took refuge in Nîmes. Auguste Alphant was detained by his duties in Lille. With no news of her father, knowing only that their apartment had been completely destroyed on 13 October 1914 following the siege of Lille and the fires caused by the bombardments, she continued her studies at the old secondary school in Nîmes. Integrating well with her fellow pupils, Amélie Alphant appreciated the atmosphere and the working environment there.

Learning about medicine

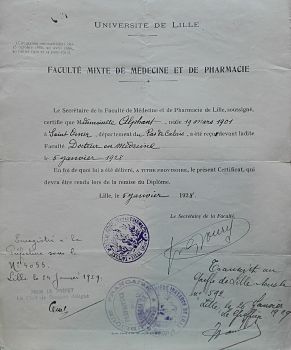

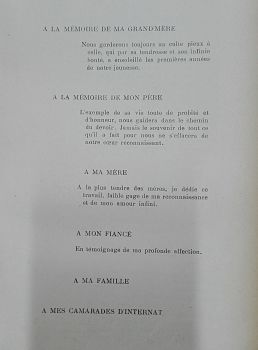

In July 1919, she was awarded a baccalauréat in Latin, languages and philosophy by the University of Montpellier. With the war over, the family moved to Lille, where Amélie enrolled at the Faculty of Science to obtain her certificate in physical, chemical and natural (‘PCN’) studies, enabling her to continue her studies in the autumn of 1920 at the Combined Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy. With a literary background, Amélie Alphant excelled, finishing in 5th placeout of 40 and graduating with distinction.

While studying at the Combined Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Amélie Alphant admitted to having been subjected to remarks by a few pretentious elders and attempts to discourage her from attending certain classes ‘on the pretext that she was a young girl’, but took no notice.

First admitted to the practical placement programme in 1922, Amélie Alphant went on to win the Lille hospital internship competitive exam in 1924 and became an intern at Hôpital Saint-Sauveur. While she was the second woman to pass this competitive exam[2],she was the first to complete her internship in Lille.

Between 1922 and 1927, she worked with Professors Henri Gaudier (surgical clinic), René Le Fort (children’s surgical clinic), Georges Carrière (children’s medical clinic), Oscar Lambret (surgical clinic) and Émile Delannoy. It was in 1925, while working in the medical clinic department at Hôpital Saint-Sauveur under Professor Georges Lemoine, that she co-wrote what was probably her first article with Dr Edmond Doumer, entitled ‘Rhumatisme cardiaque évolutif et myocardie’ (Evolving cardiac rheumatism and myocarditis), which was published in La Gazette des hôpitaux. On 1 March 1926, Amélie Alphant became a ‘préparateur’ (lab assistant) in pathological anatomy at the Faculty, working alongside Professor Ferdinand Curtis.

On 5 January 1928, Amélie Alphant defended her doctoral thesis on acute pulmonary infections in children treated by vaccinotherapy. Her thesis supervisor was Professor of Therapeutics Jean Minet. The other members of the defence jury were Professor of Pathological Anatomy and General Pathology Ferdinand Curtis and Professor of Medical Physics Emmanuel Doumer.

A close-knit couple

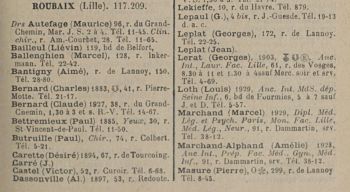

During her training, Amélie Alphant had to administer an injection to a medical student with a health problem, Marcel Marchand. Following this meeting, the two young people never left each other’s side. They became engaged and married a few weeks after Amélie Alphant defended her thesis on 14 April 1928. The following year, Marcel Marchand defended his doctoral thesis on the microscopic diagnosis of the drowning of vital organs, which was presented to a jury chaired by Jules Leclercq, Professor of Forensic and Social Medicine. That same year, the couple moved to Roubaix and set up business at 91 rue Dammartin. Amélie Alphant-Marchand provided consultations in gynaecology and children’s medicine, while continuing to assist with courses and lectures in pathological anatomy and general pathology at Lille’s Combined Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy. As for her husband, he specialised in forensic medicine and neurology, and also held a teaching post at the same faculty. To their great regret, the couple never succeeded in having children, and despite all their research, nothing could explain the problem. They then transferred their affections onto their nephews and young cousins.

Lille Institute of Forensic and Social Medicine

In 1932, they moved to 76 rue Jean Bart in Lille on the advice of Professor Jules Leclercq, who was planning to set up a major forensics department within his future institute, and wanted them to be involved in the project. The Lille Institute of Forensic and Social Medicine was inaugurated on 27 May 1934, during the 19thFrench-language congress of forensic medicine that was held there. Amélie Alphant-Marchand was in charge of the Institute’s Anatomical Pathology Department. The importance attached to this department was one of the special features of the Lille Institute. To those close to her, she explained her work as follows: ‘I had the satisfaction of creating a forensic pathology department within the new institute. The microscope had to be used to study all injuries, whether in the context of criminal investigations or common law investigations, road accidents, industrial accidents, etc.’. The pathological anatomy laboratory run by Amélie Alphant-Marchand was essential for carrying out forensic autopsies and providing all the required histological diagnoses and toxicological analyses. Amélie Alphant-Marchand played an essential role in the work of her colleagues, carrying out the analyses and examinations required to advance their work.

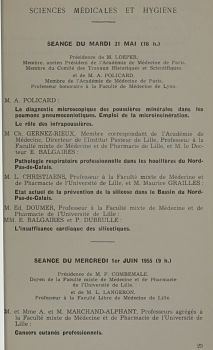

For Amélie Alphant-Marchand and her colleagues at the Lille Institute of Forensic and Social Medicine, conferences on forensic medicine provided an opportunity to present the results of their research. In 1934, in collaboration with Dr Louis Gernez, she presented a remarkable paper entitled "Histological study of the effect of pregnant women’s moods on the male genital glands of young rabbits’. Is it possible to diagnose the sex of a foetus during pregnancy using hormonal methods?’. Over the course of her career, Amélie Alphant-Marchand has published numerous papers, articles, lectures and presentations, sometimes on her own and sometimes in collaboration with other colleagues at the Combined Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy. She frequently collaborated with her husband, Marcel Marchand.

In the 1930s, Amélie Alphant-Marchand and her colleagues were particularly interested in lung damage, especially in the event of drowning. In 1936, her career took a new turn. She became an ‘assistante’ (junior member of the faculty’s teaching staff) in forensic and social medicine at the Lille Institute of Forensic and Social Medicine. At the same time, she continues to provide paediatric and gynaecological consultations from her home.

The Second World War disrupted operations at the Lille Institute of Forensic and Social Medicine. In May 1940, Amélie Alphant-Marchand evacuated Lille for Grignan in the Drôme region. Meanwhile, Marcel Marchand was assigned to the 2ndArmy of Amiens in laboratory Z no. 342. Demobilised on 20 August 1940, he joined his wife in Valence.

During the Occupation, the Lille Institute of Forensic and Social Medicine was fully occupied by the Germans. Action needed to be taken to enable doctors to use the first floor of the left wing again. The Institute’s departments moved back in and the pathological anatomy laboratory was reformed in December 1941, following Amélie Alphant-Marchand’s return to Lille. In May 1944, the staff of the Lille Institute of Forensic and Social Medicine, anticipating the approach of active military operations and fearing new German requisitions, quickly safeguarded the pathological anatomy laboratory equipment that was likely to be of interest to the Germans at the Marchand-Alphant household, located at 76 rue Jean Bart. The following week, all the Institute’s equipment was installed on the premises of the Combined Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy. The Institute of Forensic and Social Medicine was hit by the bombings of 10 May and 20 June 1944. This second bombardment destroyed the top two floors of the Institute’s left wing.

Participation in the development of a new disciplinary field: occupational medicine

During the Second World War, the Lille Institute of Forensic and Social Medicine strengthened its competencies and services in occupational medicine. In June 1942, the Association de la médecine du travail et d’hygiène industrielle de la région du Nord (Occupational Medicine and Industrial Health Association for the Nord Region) was created. This research company, one of the Institute’s own departments, was concerned with the prevention of accidents and occupational illnesses, and with industrial health. At the Institute and the Combined Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, it organised information conferences for doctors, occupational physicians, labour inspectors, social workers, labour social advisors, and employers’, workers’ and executives’ associations. Marcel Marchand was heavily involved in the association, but Amélie Alphant-Marchand also regularly gave lectures.

In 1946, a Chair of Occupational Medicine was created at the Lille Combined Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy. Professor Jules Leclercq was then appointed to the position. The following year, a position for a ‘chef de travaux’ (senior researcher) in occupational medicine was created. Marcel Marchand held this position until 1 JanuaryJanuary 1950, when he was appointed Associate Professor of Forensic Medicine. His wife, Amélie Alphant-Marchand, succeeded him as ‘deputy senior researcher’ in occupational medicine. This was a turning point in her career. This marked the start of a fruitful collaboration between Amélie Alphant-Marchand and Professor Louis Christiaens, who had just succeeded Professor Jules Leclercq.

In 1947, in recognition of her work as director of the pathological anatomy laboratory, Amélie Alphant-Marchand was promoted to the rank of ‘officier’ of public education.

During this period, the Marchand-Alphant couple frequently worked together. They often took part in the same congresses and other professional meetings, both in the Lille area and abroad. Amélie Alphant-Marchand’s work often focused on a health issue that was very prevalent among the region’s miners at the time: silicosis. At the same time, Marcel Marchand pursued his dual career with the Labour and Workforce Inspectorate and the Lille Combined Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, where he became a professor in 1960.

Amélie Alphant-Marchand applied for retirement on 1October 1964. Marcel Marchand continued his academic career for a few more years. He was appointed Honorary Professor in 1972. Following a fall, he died suddenly on 23 August 1984. Amélie Alphant-Marchand decided to leave Lille and move to a retirement home in Le Chesnay (Yvelines). She died there on 2 October 1997.

Concerned about the place of women in society, Amélie Alphant-Marchand was a member of the Soroptimist Club de Lille, which ‘takes action to change the rules, break down stereotypes and improve women’s lives’. She regularly attended meetings organised by this movement, in the company of her friend Jeanne Sales-Decoulx, who was also a doctor. Amélie Alphant-Marchand had the following to say about the role of women:

‘I believe, as far as the liberal professions are concerned, that women must make a choice based on what they want to do, without worrying about influences and advice, and also to be sufficiently aware of their value and what they are capable of. Many women doctors are content with administrative positions, school medicine, social security, etc. All because for a long time, and especially during this detestable 19th century, we have been sayingthat women can’t do what men can! The story of the first female doctors in France is extraordinary and tells us a lot!’.

Notes written by Nathalie Barré-Lemaire.

Notes

[1] Amélie Alphant-Marchand was the first cousin of Marie-Andrée Lagroua Weill-Hallé (1916-1994), who was a gynaecologist and the founder and president of La Maternité heureuse (1956-1967).

[2] Gabrielle Cantrainne was the first female winner of the Lille hospital internship competition. The daughter of farmers, she was born in Robecq in 1889 and attended secondary school in Saint-Omer. In 1906, she obtained a baccalauréat in foreign languages from the Lille Faculty of Arts. Despite passing the Lille hospital internship competitive examination in 1911, she never submitted her doctoral thesis.

Sources

Nord Department Archives

Lille Combined Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy personnel file - 3657W11.

Lille Combined Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy student file - 2894W63.

University of Lille photo album, circa 1937 – 85Fi.

University of Lille, Health UL - Learning Centre

Doctor of Medicine thesis - B 55.375-1928-13.

BIU Santé, Paris

Photographs of the Hôpital Saint-Sauveur in Lille - 45/101.

gallica.bnf.fr/National Library of France

Digitised publications: Candide, Rosenwald Guide, Eightieth national congress of learned societies, Lille, 31 May - 4 June 1955: session agenda (French Ministry of Education. Historical and Scientific WorksCommittee, 1955).

Lille Municipal Library

Rue de Tournai in Lille in 1914 - CP 118.

The author would like to thank Isabelle Korda for her invaluable help.