A Russian student at the Combined Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy

Dweira[1] Bernson was born on 3 January 1871 in Brest-Litovsk, Belarus, which was at that time part of the Russian Empire. She was born into a Jewish family. By this time, it was becoming difficult for this community to access higher education. From 1887 onwards, the Russian administration imposed a numerus clausus restricting the admission of Jews to universities. The desire to study led them to emigrate.

Nothing is known of Dweira Bernson’s past, in particular when she arrived in France. The first document to mention her refers to the academic year 1895-1896: that year, she passed the first part of the second medical doctorate examination, with a grade of ‘highly satisfactory’.

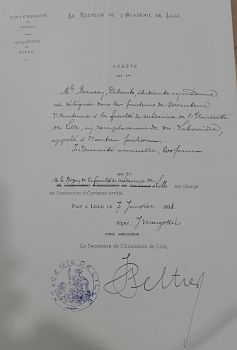

While still a student, she was appointed ‘anatomy instructor’ at the Combined Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy by decree on 7 January 1898[2]. She was the first woman to hold this position at the University of Lille. She had already reached an advanced stage in her studies, and the local press, Le Grand Écho du Nord de la France,mentionedhersuccessin the3rd, 4th and 5th doctoral exams.

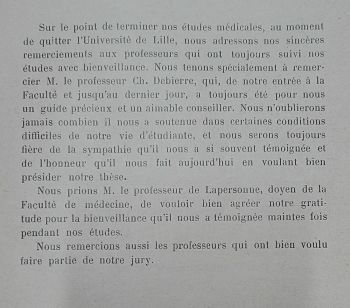

Dweira Bernsonworked alongside anatomy professor Charles Debierre[3].She extended special thanks to him in the dedications section of her thesis. He ‘supported me through some of the challenging conditions that formed part of our lives as students’. While Dweira Bernson was certainly referring to the pedagogical and scientific support that Charles Debierre was able to provide, it’s also conceivable that she was referring to the financial support that came with the instructor’s position. She appears to have had no family in Lille, so it’s possible that this job enabled her to complete her university studies.

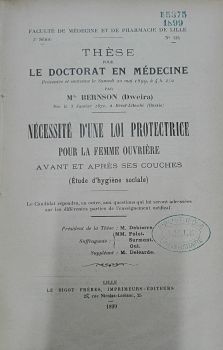

‘The Need for a Protective Law for Working Women Before and After Childbirth (SocialHealth Study)’. The jury members were Professor Charles Debierre, Henri Folet, Professor of Clinical Surgery and former Dean, Hippolyte Surmont, Professor of Health, Marcel Oui, agrégé (someone who has passed the agrégation competitive teaching exams) for Childbirth Classes and Albert Deléarde, agrégé. All these specialists were keenly interested in social health, obstetrics and paediatrics, and were probably in favour of women entering the medical profession. At the defence, the audience was made up of a dozen people, including a journalist from L’Égalité de Roubaix-Tourcoing,a socialist daily newspaper. It recounts the ‘sometimes harsh’ comments made by Dweira Bernson and the jury’s reactions, particularly Charles Debierre’s support.

Notes written by Nathalie Barré-Lemaire.

A career focused on early childhood

On 11April 1900, Dweira Bernson and Désiré Verhaeghe were married in Ixelles, Belgium[4]. Dweira had been staying there for about six months, perhaps for professional reasons. They soon returned to Lille, where Désiré Verhaeghe was head of the ophthalmology clinic at the Combined Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy. At the same time, he took charge of the Émile Roux dispensary, set up by Albert Calmette, at that time the director of the Institut Pasteur in Lille, and became involved with the Workers’ Health Secretariat of the Lille Stock Exchange, for which he provided medical consultations at the Coopérative de l’Union, place Vanhoenacker. He was in charge of the magazine La Médecine sociale,which was a monthly bulletin published by the National Union of Social Medicine and body of the International Committee for the Defence of the Rights of the Sick and of Workers’ Health.

As early as 1902, the local press reported on Dweira Bernson’s various activities. It is notable that she continued to use her birth name. In February 1902, she was provisional secretary of the new Lille-based association ‘La Goutte de Lait du Nord’. The aim of this association was to combat infant mortality. At that time, newborns were hard hit by athrepsia and gastroenteritis, which were largely responsible for their deaths. The aim was therefore to achieve a better quality diet for the little ones by encouraging breastfeeding, distributing high-quality sterilised milk to women who couldn’t breastfeed or could only partially breastfeed, and ensuring medical follow-up for mother and child. Dweira Bernson provided medical consultations for ‘La Goutte de Lait du Nord’. In 1905, she presented a report on the work of this organisation in theEchomédical du Nord.

She held other positions at the same time. In 1902 and 1903, advertisements in the local press stated that she provided consultations for women’s and children’s illnesses at the Hôtel Ferraille in Roubaix, as well as in Lille at 67 rue d’Artois, then at 249 rue Solférino. She was also in charge of medical services for Lille’s municipal crèches.

The 22 June 1903 issue of the newspaper L’Égalité de Roubaix-Tourcoingpresents Dweira Bernson’s recently published report on the running of the municipal crèches in 1901 and 1902, in particular the one located on Place Déliot in a working-class district of Lille. Dweira Bernson not only points out the failings of this system, but also the difficulties encountered by working-class mothers as a result of ‘capitalist competition’, leading some to voluntarily neglect their children.

That same year, she and her husband came to the aid of workers injured in a crane accident on boulevard Victor Hugo, near their home.

On 26September 1904, Dweira Bernson gave birth to their only daughter Reysa[5].

In 1912, she opened a clinic for women’s diseases at Professor Emmanuel Doumer’s clinic at 28 rue Saint-Sauveur in Lille. She received visitors for two hours, three days a week. Like many doctors during that period, she worked several jobs at the same time, offering consultations in different locations.

During the Great War, Désiré Verhaeghe was mobilised. Remaining in Lille, Dweira Bernson worked as a ‘lady visitor for rescued children’ with Dr Alphonse Hamel, departmental inspector for public assistance. By the end of the war, she was the only female doctor offering children’s consultations, which were organised by the Comité d’assistance des régions libérées (Liberated Regions Assistance Committee). She was assigned to the rue des fossés area in Lille.

‘Doctor Bernson’[6] was a well-known figure locally. So when, in September 1922, a large delegation of French and Belgian professors and doctors visited the Saint-Amand thermal baths, she was one of a handful of doctors clearly identified by E. Polvent, a journalist at L’Egalitéde Roubaix-Tourcoing.

Meanwhile, Désiré Verhaeghe, who in 1919 became deputy to Lille mayors Gustave Delory and then Roger Salengro, died on 14 April 1927. The couple were separated, but not divorced. Désiré Verhaeghe lived in another home, probably as a live-in partner and father of a young son. The press offered its condolences to his widow and children. Given Dr Verhaeghe’s local reputation, this is unlikely to be a mistake. The funeral was a grand affair, with a huge procession accompanying the deceased to the cemetery, with no mention of the family’s presence.

Raising awareness of health issues

During the 1920s and 1930s, Dweira Bernson was particularly active, writing countless articles to demonstrate her commitment to the causes she believed in. First and foremost, she defended the cause that was particularly dear to her: protecting infants and improving their living environment. In 1925, for example, in Le Grand Écho du Nord de la France,she signed a section entitled ‘A few tips for mums to help their little ones develop properly’. She explained the damaging effects of swaddling, pacifiers and the influence of food and medication taken by the person nursing the child on children’s health. At the time, Dweira Bernson was a ‘medical inspector’ for young children in Lille. On 31 October 1934, Le Grand Écho du Nord de la France published a letter she sent to the mayor of Lille in an article entitled ‘Preventing Unhappy Childhoods’.In response to reports of children being forced to beg alongside their parents, Dweira Bernson explains the interest of various movements in defending children’s rights, and proposes that parents be required to entrust their children ‘depending on their age, to a school or crèche within the limits of opening hours’.

Le Grand Écho du Nord de la France relayed her concerns by reprinting excerpts from articles and communications, then publishing an article signed ‘Doctor Bernson’. In it, she advocated the strict application of article 5 of the May 1933 law ‘by obliging parents or guardians to declare to the mayor of the commune where they intend to have the child educated in the month in which the child reaches the age of six’, as well as the mandatory reporting of ‘delinquent children to the authorities by school principals’. She highlighted measures taken by cities such as Roubaix, which punishes negligent parents, and hoped that Lille would adopt similar measures. Dweira Bernson was also interested in women’s health. In August 1926, for example, she spoke out in the local press against the use of women to pull boats on canals and rivers. In it, she expressed her astonishment at the lack of press interest in the issue, despite the fact that numerous articles had appeared ‘pitying the poor horses used to pull these boats’. She added: ‘It may have been rightly written that an animal should not be continually employed in such work, but how can it be accepted that human beings, women, should do it?’ In the article, she describes the harmful health consequences of this activity, before concluding by calling on the Prefect of the Nord region to put an end to it by decree, pending legislation. Concerned about the working classes, she sent a letter to the press, again published by Le Grand Écho du Nord de la Franceon 7 May 1937, under the headline ‘We should create a “bric-a-brac office”’. In it, she denounces the accumulation of useless items cluttering up attics, which could help families of modest means save on housing costs by enabling them to rent an empty apartment rather than a more expensive furnished one. She then called for the creation of a municipal bric-a-brac office ‘which would collect all the furniture, utensils, clothes, etc. that individuals would be willing to give up, and then distribute them to families in need after cleaning them and carrying out any necessary repairs’.

Dweira Bernson’s last known championed cause: tackling noise pollution.She published articles on the subject, notably in L’Égalité Roubaix-Tourcoing in 1938 and 1939, including some with evocative titles, such as‘Let’s kill the noise before it kills us...’. In it, she stressed the harmful influence of noise on ‘subjects who are predisposed to mental imbalance’ and on children. She relayed the warnings of the medical profession and stressed the depressing effect of noise on the nervous system. Drawing a parallel with sight, she emphasised the importance of hearing and the need to maintain normal perception of this sense. She described the unbridled use of horns and the inaction of the legal system, despite municipal bylaws. Lastly, she called for a ‘law that would apply throughout the territory of the Republic, prohibiting the use on public roads of any horn exceeding a maximum intensity, as yet to be determined’.

In the last article she signed (to our knowledge) on 11 August 1939 in L’Égalité Roubaix-Tourcoing,she wrote a phrase that symbolises who was as a person and her struggles: ‘I’ll return to this matter and insist without hesitation because we can’t hammer the point home enough when public health is at stake – as it is in the fight against noise – and will continue to do so until the public authorities decide to take action to deal with the issue’.

In January 1940, she took part in a fundraising campaign to buy blankets for soldiers. In the newspaper L’œuvre where she is mentioned, she is referred to as ‘Doctor Bernson – widow Verhaeghe’. This is one of the very few times she uses her married name.

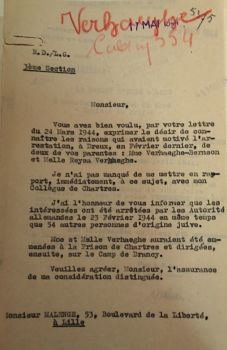

Dweira Bernson does not reappear in sources until 1944, following her arrest with her daughter Reysa in Dreux on 23 February. The reason for their arrest was their Jewish origin. Taken to the Chartres prison, they were transferred the next day to the Drancy camp. Convoy 69 left Drancy for Auschwitz on 7 March 1944. Their family’s efforts to save them came too late. Madeleine Malengé-Dorchies[7] and her husband Émile were unable to send Désiré Verhaeghe’s baptismal certificates on time. Dweira Bernson and her daughter Reysa would never return from Auschwitz.

It’s likely that, as a highly committed and certainly divisive figure from Lille, sympathetic towards socialist and Marxist ideas, she had people who disliked her and even ‘enemies’. What’s more, given her previous involvement, she was unlikely to have remained inactive during the Second World War. In addition, although she was a non-practising Jew, she may have had to flee Lille to regain a certain degree of anonymity, which could explain her presence in Dreux in 1944.

Dweira Bernson was a dedicated woman! While this character trait had been apparent since her medical doctorate, she had always stayed true to her beliefs and never ceased to use all her energy to communicate these beliefs to a wide audience.

Notes

[1] The first name Dweira is the Yiddish version of the first name Dvorah, Gallicised as Déborah.

[2] The anatomy instructor assists the teacher during dissection sessions.

[3] Since 1896, Charles Debierre (1853-1932) was also first deputy of the mayor of Lille, Gustave Delory, and hospice administrator. Charles Debierre was a member of the radical-socialist party. A Dreyfus supporter and Freemason, he founded the Université Populaire de Lille in 1901. He subsequently held national office as Senator for the Nord region from 1911 to 1932, Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Radical and Radical-Socialist Party from 1917 to 1918, and elected Chairman of the Convent of the Grand Orient de France in 1918.

[4] The marriage certificate does not mention the presence of Désiré Verhaeghe’s family. However, it is important to note that Désiré Verhaeghe’s siblings, who were of Catholic origin, accepted this union. Désiré Verhaeghe was a witness at his brother’s weddings in 1899 and 1902.

[5] Reysa is the first name of Dweira Bernson’s mother. This was her way of showing her attachment to her origins.

[6] This was how she was generally referred to in the press, and the name she regularly used to sign her articles.

[7] Madeleine Malengé-Dorchies is Dweira Bernson’s niece by marriage.

[8] Dweira Bernson was the only female doctor of her generation, along with Berthe Grimpret, to practise in Lille at the time.

Bibliography

Danielle Delmaire and Jean-Michel Faidit, ‘Vie et mort de deux femmes juives. In the shadow of a husband and father’, Tsafon [Online], 74 | 2017, published online 31 May 2018, accessed 14 November 2019. URL: journals.openedition.org/tsafon/405; DOI: 10.4000/tsafon.405

Juliette Estaquet, Un texte scientifique et politique inscrit dans son temps : Regards sur le thèse de médecine de Déborah Bernson, Nécessité d’une loi protectrice pour la femme ouvrière avant et après ses couches, Lille, 1899,Mémoire de Master 1 Culture et Patrimoine, supervised by Judith Rainhorn, University of Valenciennes and Hainaut-Cambrésis, 2011-2012.

Sources

Nord Department Archives

Lille Combined Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy personnel file - 2894W53.

Survey of the Moulins district crèche, Place Déliot, Lille, 1903 - M149/93.

Correspondence from the Inspection de l’Assistance Publique du Nord, 1916 - 9R251.

Nominal roll of personnel employed in clinics set up and subsidised by the Comité d’assistance des régions libérées, 1918-1919 - Xsuppl/113490.

File relating to the arrest of Dweira and Reysa Bernson, 1944 - 1W1879.

University of Lille, Health UL - Learning Centre

Doctor of Medicine thesis - B 55.375-1899-124.

BIU Santé, Paris

Photographs of the Hôpital Saint-Sauveur in Lille - CISB0282, CISB0284, 45/101.

gallica.bnf.fr/National Library of France

Digitised press: Le Grand Écho du Nord de laFrance, L’œuvre.bn-r.fr/Bn-R

- Roubaix Digital Library

Digitised press: L’Égalité deRoubaix-Tourcoing, La Croix deRoubaix-Tourcoing, L’Avenir deRoubaix-Tourcoing, Le Journal deRoubaix.

The author would like to thank Danielle Delmaire for her help and invaluable advice.