A young girl not quite like the others..

Louise Marie Henriette Jeanne de Bettignies was born in Saint-Amand-les-Eaux on 15 July 1880. Her family originated from Tournai. She was the second-to-last of nine children born to Henri-Maximilien de Bettignies and Julienne Mabille de Poncheville. His father was director of a porcelain and ceramics factory until a reversal of fortune forced him to sell the family business and become a sales representative. The family moved to Lille in 1895, to 166 rue d’Isly.

She completed her secondary education in Valenciennes with the Sisters of the Sacred Heart. At a very young age, she already showed an assertive, independent character. According to her cousin André Mabille de Poncheville:

Louise was blonde, frail-looking, with an animated face and piercing eyes that seemed to roam everywhere. She couldn’t stand still(1).

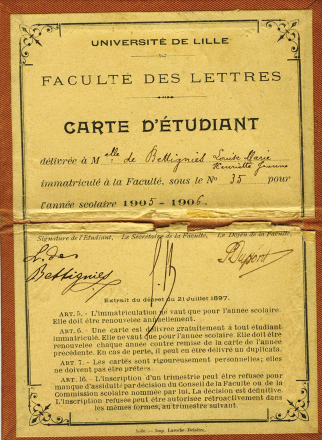

In 1898, at the age of eighteen, she was about to take her brevet supérieur final exams. But she was a year early, and the administration refused to make an exception. Louise de Bettignies decided to continue her studies in England, and soon after enrolled at Oxford University. She led a relatively independent life that suited her character. But in 1903, on the death of her father, she decided to return to study in France and enrolled at the Faculty of Arts in Lille. She obtained her qualification in English in 1906.

During this period, she joined the Catholic Patriotic League of French Women, an association created to support Catholics who had rallied to the Republic. A highly active member, she distributed the magazine to members, collected subscriptions and kept the magazine files up to date. But she also had to think about earning a living. Armed with her precious qualifications, Louise de Bettignies found a job as a tutor. Her perfect command of English, Italian and German, as well as her knowledge of Russian, Czech and Spanish, enabled her to attract the attention of wealthy employers. Indeed, French tutors were highly valued and well paid abroad. She soon entered the service of Count Visconti de Modrone in Milan and, in 1911, Count Mikiewsky in Galicia. Prince Carl Schwarzenberg, then Princess Elvira of Bavaria, enlisted her services. Her various positions allowed her to travel extensively and to mingle with members of Europe’s high-ranking aristocracy. She was even offered the chance to educate the children of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the imperial throne of Austria-Hungary, but refused and returned to France.

A patriotic commitment right from the outbreak of war

In early 1914, she underwent an operation for appendicitis and returned to live with her mother in Lille. It seems she was thinking of joining the Carmelites religious order. The declaration of war surprised her, occurring while she was staying in a villa in Wissant. The German breakthrough was rapid and Lille was soon under bombardment. Louise de Bettignies returned to Lille and lived on rue d’Isly with her sister Germaine. They were both recruited as nurses and helped out in the districts affected by the flames. Louise cared for the wounded at the Parvis Sainte-Catherine hospital. She used her language skills to write letters from wounded Germans to their families. Under enemy fire, she did not hesitate to supply the city’s defenders with food and ammunition. Nevertheless, Lille fell. The town was occupied for the duration of the war.

Louise de Bettignies could not stand to remain powerless while her country continued to fight and her town was occupied by the enemy. All the more so as the occupation was to prove particularly trying for Lille. The resistance began to organise. The occupied zone was completely cut off from the rest of France. Families were left without news of their men at the front and of their loved ones who had fled the German advance. Young women were recruited to find routes to carry mail to the free zone. They then hid messages under their skirts to avoid being searched. Louise’s sister Germaine agreed to take part, and crossed over into the free zone, where she then stayed. Louise de Bettignies remained in Lille by herself and also smuggled mail through the German lines. At Péronne station, she was almost arrested and only saved by an unexpected meeting with Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, whom she had met on her travels. They had played several games of chess together! Thanks to the Prince’s intervention, she continued her journey through Belgium, the Netherlands and England. The only way to reach France was to bypass the front by crossing the Channel. On her arrival in Britain, she was interrogated by the intelligence services, who were impressed by her courage, language skills and patriotism. They asked her to enter their service, but Louise de Bettignies refused. At that time, spies were viewed in much the same way as prostitutes.No wonder she refused. Besides, she preferred to work for her own country. Upon returning to France, she was also contacted by the French secret service. She was able to provide them with up-to-date information on the occupied zone. However, the French services did not often work with women. The French did not consider espionage to be a respectable activity for women. Not to mention, the French services offered no training and did not advance any funds. Travel expenses were reimbursed upon presentation of an invoice! Under these conditions, Louise de Bettignies considered accepting her offer from the British. It was on the way back to Lille that she agreed to work for the British secret service, in agreement with the French secret service. In just a few days, she was introduced to the basics of espionage in Folkestone, then returned to Lille.

The Alice network

Under the pseudonym of Alice Dubois, an employee of an import-export company in Free France, she and her friend Léonie Vanhoutte, known as Charlotte Lameron, set up a vast intelligence network in northern France. The Alice network (or Ramble to the British) was born.

Louis de Bettignies took all kinds of risk to deliver quality information to the Allies. She did not hesitate to disguise herself as a German officer to travel from Armentières to Saint-Omer. In total, up to a hundred agents and collaborators were involved in the Alice network. Although it’s difficult to assess the exact extent of her contribution, given the secrecy that naturally surrounded her actions, the Alice network seems to have been the most extensive and effective. It helped to save a thousand British lives. The network centralised information on German operations and organised border crossings of men, information, mail and the underground press. Louise de Bettignies herself travelled all the way to England to bring back information, cleverly hiding it in the hems of her handbag or clothes, or wrapped around the stays of her corset, or in her hair. The Alice network even managed to communicate to the Allies the day and time of the German emperor’s passage through Lille, even though the bombing of the imperial train ultimately failed. Her information helped predict the future German attack on Verdun, which the French high command did not take seriously.

Unfortunately, Louise de Bettignies was arrested by the Germans at a checkpoint near Tournai and imprisoned in Brussels on 20 October 1915. She was subjected to several violent interrogations by German officers, who bruised her ribs and broke several of her teeth. Despite being confronted by several witnesses, she remained silent and refused to denounce anyone.Her trial took place on 16 March 1916, and she was sentenced to death. Her sentence was commuted to hard labour for life. As she was transferred to the Sieburg fortress in Germany, she was given an honourable mention in the ‘ordre de l’armée’ by Marshal Joffre for her actions (20 April 1916).

Imprisoned in Germany

In this women’s prison, daily life is austere, food is inadequate and anything beyond the bare essentials has to be brought in from outside by the prisoners at their own expense. The days spent plagued by hunger and cold are brightened only by parcels and letters from the prisoners’ families. However, Louise de Bettignies did not give up. According to the Princess of Croÿ, who was with her at the time:

‘Many times she was punished for insubordination or fomenting revolts’.

Louise de Bettignies discovered that the Germans were having the prisoners make grenade heads to be used against French soldiers. The Hague Convention prohibits the use of prisoners to manufacture weapons against their own homeland, and Louise knows this and makes it known. She refuses to work and draws the other prisoners into her revolt. She was then sent to solitary confinement for 48 hours without wool, blankets or even food. Her cell was a chilly cage 1.40m in width and length (including the toilet!). All she had to rest on are straw cushions and there was no view of the outside world, as iron shutters blocked out any light.

Despite this treatment, Louise de Bettignies did not give up, and the revolt continued. The Germans were forced to give up. Louise saw her benefits cut. She would no longer receive letters or parcels. Still she refused to work for the enemy, despite threats to cut off her food supply. Her spirits remained high, but her health was failing.

In early 1918, her condition deteriorated severely. At first, she received little care. But as her condition worsened, she was belatedly transferred to Cologne for surgery inhorrifically unsanitary conditions. Dying as a result, she came to regret not having been shot. She died on 27 September 1918, too soon to see the victory that she had helped bring about.

National heroine

In 1920, her remains were repatriated. On 16 March of the same year, at a solemn funeral in Lille, she was awarded the Légion d’Honneur, the Croix de Guerre and the British Military Medal. She was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire. She was buried in Saint-Amand-les-Eaux.

Since the end of the war, her memory has been kept alive in the Nord region.A sculpted monument by Real del Sarte was erected in her memory on boulevard Carnot at the entrance to Lille in November 1927. Recognised as a national heroine, many streets and schools bear her name. She has inspired filmmakers and novelists alike.

Notes written by Sarah Lagache.

The author wishes to thank the family of Louise de Bettignies for their help in writing this biography.

Notes:

[1] André Mabillede Poncheville (23May1886 - 20May 1969), La Voix du Nord of 30 September 1967.

Sources:

Birth certificate, Nord Department Archives (1 Mi EC 526 R 002)

Lille Faculty of Arts student file, Nord Department Archives (2640W23)

Legion of Honour file, National Archives (LH//227/34)

Bibliography:

Chantal Antier,Louise de Bettignies : espionne et héroïne de la Grande guerre, 1880-1918, Paris, Tallandier,“‘Biographies’ collection, 2013